Blog

Resource governance and post-extravism

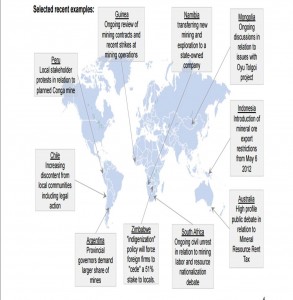

Sitting in a two day workshop on Resource Governance convened by the International Resource Panel, in Davos. While the snow falls all around us, I am struck we are having this discussion within a country that is used as a base by the largest commodity traders in the world, and where the bulk of the profits from mining in Africa land up, for investment elsewhere. The concept note is written by an amazing Mozambican based in Rwanda, Antonio Pedro, who works for the UN Economic Commission for Africa. Its a remarkable overview of the challenge from what could be called a neo-extractivism perspective, i.e. a critique of exploitative extravism that contributes little. The result is the contestations of mining reflected in the World Economic Forum diagram attached to this post. Using the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, Pedro is arguing for quite radical changes that will make mining and their products contributors to sustainable development. He started his presentation by reminding us all about the Marikana massacre. But his paper does not question the right of the extractive industries to exist. Hopefully the Latin American representatives here will introduce the notion of post-extrativism, i.e. a transition to diversified economies premised on reduction of dependence on and eventual closure of extractive industries. The ECLAC representative in his opening did refer to ‘resource nationalism’ – that term is current on the African continent, but it can mean two things – neo-extrativism (i.e. how to capture more benefits from extractivism), or post-extravism (using resource rents to fund the transition to diversified economies not dependent on extractivism).

Sitting in a two day workshop on Resource Governance convened by the International Resource Panel, in Davos. While the snow falls all around us, I am struck we are having this discussion within a country that is used as a base by the largest commodity traders in the world, and where the bulk of the profits from mining in Africa land up, for investment elsewhere. The concept note is written by an amazing Mozambican based in Rwanda, Antonio Pedro, who works for the UN Economic Commission for Africa. Its a remarkable overview of the challenge from what could be called a neo-extractivism perspective, i.e. a critique of exploitative extravism that contributes little. The result is the contestations of mining reflected in the World Economic Forum diagram attached to this post. Using the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals, Pedro is arguing for quite radical changes that will make mining and their products contributors to sustainable development. He started his presentation by reminding us all about the Marikana massacre. But his paper does not question the right of the extractive industries to exist. Hopefully the Latin American representatives here will introduce the notion of post-extrativism, i.e. a transition to diversified economies premised on reduction of dependence on and eventual closure of extractive industries. The ECLAC representative in his opening did refer to ‘resource nationalism’ – that term is current on the African continent, but it can mean two things – neo-extrativism (i.e. how to capture more benefits from extractivism), or post-extravism (using resource rents to fund the transition to diversified economies not dependent on extractivism).

Related to this resource governance discussion is a new report released by the IRP yesterday entitled International Trade in Resources. This amazing report led by Marina Fischer-Kowalski shows that there is a declining number of countries that are still net exporters of resources and a rising number who are net resource importers. If these trends continue, the world will face increasing instability. I cannot help thinking that we need a UNFCC for resources – a global resource governance agency where the terms of future resource extraction and use are negotiated and managed. These resources are, after all, part of the commons. Should they continue to be exploited for the benefit of the few?

Italy’s Enel and Germany’s EON SE decide to move out of fossil fuels

I was stunned today by the Facebook post showing Kumi Naidoo, head of Greenpeace, shaking hands with Franceso Starace, the new CEO of Enel, one of Italy’s largest energy utilities. Like Germany’s EON SE, Enel is committing to closing 23 coal-fired power plants in Italy and cancelled plans to build two new ones, one in Italy and one in Chile. Both companies have clearly taken a long-term strategic view and taken into account that while the costs of coal and nuclear are rising everywhere, the costs of renewables are dropping fast. Unlike ESKOM, they both have to worry about profits to survive and realize, therefore, that repairing rather than destroying the planet makes good business sense. ESKOM’s recent announcement that it will stop supporting the growth of the renewable energy sector stands in direct contrast to this far-sighted strategy of companies that are in the same business as ESKOM. And if one considers the facts, ENEL and EON SE must be right. Renewable energy expanded at its fastest rate ever in 2014

(Source: International Energy Agency 2015)

(130 GW), despite the decline in oil prices which many predicted would halt the extra-ordinary growth in renewables world-wide. Renewables accounted for more than 45% of net additions to world capacity in 2014. Based on current trends, renewables which accounted for 22% of total capacity in 2013 are expected to rise to 26% in 2020. In other words, two thirds of net additions to power capacity by 2020 will be renewables (International Energy Agency 2015). Wind power now globally costs the same as coal power. The above prices need to be seen in the context of average prices for coal-fired electricity in 2015: increasing from $66 per MWh to $75 in the Americas, from $68 to $73 in Asia-Pacific, and from $82 to $105 in Europe. Given the rising real cost of Medupi (from R70 billion initially, to R300 billion in the end, according to some well-informed people), renewables are effectively at grid parity per MWh in South Africa. As far as investment trends are concerned, 2014 was the fifth consecutive year that investment in renewables exceeded investment in new fossil fuel-based energy – by 2014 it was up to USD 242.5 b compared to the USD 132 b invested in new fossil-fuel based capacity in the same year (International Energy Agency 2015). What really hit me hard is a statement by Starace that conventional fossil fuels and nuclear power plants are “a trap … A trap for companies to die.” What does he mean? He is referring to massive risks involved in large projects – “Big is bad”, he said, “Our strategy is much more flexible and modular than it was before, and more adaptable to the world we live in.” Now I understand something that has puzzled me since looking closely at who got the awards in Round Three of the REIPP. ENEL was awarded nearly 300 MW across a number of projects dwarfing by far all the other bidders. This is a massive amount of renewable energy. Why did they do so ‘well’? Well, to put it simply, as a corporate they could borrow against their large balance sheet and secure global finance rather than access more expensive project finance from local banks, and as a large company it can probably secure more attractive prices from equipment suppliers. This is what made it possible for them to undercut the prices of competitors and contributed to the lowering of the cost of renewable energy in South Africa. The down side is local players got squeezed out and more of the profits can get repatriated. But what I have now realized is that this is part of a global strategy by ENEL to become a dominant player in the renewable energy sector globally, taking advantage of the rapid transition to renewable energy taking place globally. As already suggested this is good and bad for South Africa: good in that renewable energy prices are pushed down, bad because it means a global corporate takes control of a sector that could be locally owned and decentralised. At least two renewable energy plants are locally owned by community trusts. Would this not be a better option? So there we have it: welcome to the political economy of the new world of renewable energy expansion and growth. And hey, maybe we should ask for Kumi Naidoo’s strategic advice – after all, he is a South African!

2015: a turning point?

Sitting in a meeting of the International Resource Panel, in Davos, Switzerland. I’ve been a member of this amazing expert panel since 2007. The Co-Chairs are now Janus Potocnik and Ashok Khosla. The recent adoption of the SDGs is regarded by many here as a game changer, making 2015 a turning point. How we manage resources is seen as affecting directly 12 of the 17 SDGs. While there is a lot the SDGs leave out, they are global goals that – unlike the MDGs – are applicable to everyone. What is interesting is that for the first time in this group, there is a strong belief that we need not only be in the business of documenting the unsustainability of the current global economy, but also transition pathways that can lead more sustainable modes of production and consumption. This is what I argued for recently in book chapter, and is well discussed in the new book by Scoones, Leach and Newell entitled The Politics of Green Transforamtions published by Routledge Earthscan. Just completed a journal article called Developmental States and Sustainability Transitions: Prospects for a Just Transition in South Africa where I try find a meeting point between the developmental state literature and the sustainability transition literature. This is now essential in an SDG world, but has not really been tackled in a substantial way. I argue that South Africa’s renewable energy revolution is a key example of what is possible.

New book on the politics of green transformations

There are very few social scientists involved in the global sustainability discussion, and this is reflected in the fact that so little of any sense gets said about the politics and social dynamics of the current polycrisis and the transitions underway to more sustainable modes of production and consumption. I have been searching for something satisfying to read in recent months that connects my social science interests to the global sustainability and ‘green economy’ discussions. Finally something has just come out that goes a long way towards what I was looking for. This is what the authors say in the Introduction: “What is often missing, however, is attention to the politics that are inevitable implied by disruptive change of this nature: questions of institutional change and policy, as well as more profound shifts in political power. This is the starting point for this book.” Ah, fresh air at last, at last! Have a look at The Politics of Green Transformations edited by Ian Scoones, Melissa Leach and Peter Newell, published by Routledge Earthscan, 2015.

Useful new reading from IDS

Institute for Development Studies has released a useful paper on accelerating sustainability transitions from a political economy perspective. Very useful overview of recent approach to sustainability. AcceleratingSustainabilityWhyPoliticalEconomyMatters

A day with Isabelle Stengers

Stengers SubjectivityWhat a pleasure to spend a day with a great intellectual-of-the-world – Stengers has seen it all, heard it all, and ends up incredibly humble, brutally honest and astoundingly unafraid during times when fear ensures the survival of so much redundancy. Starting off with a visit to Enkanini, then lunch at STIAS with the visiting fellows there, and then an afternoon seminar based on her paper entitled Experimenting with refrains: subjectivity and the challenge of escaping modern dualism, I was reminded what it means to inspire, question and probe the mysteries of what it means to be human. Written for the first edition of a new critical studies journal called Subjectivity, this paper is aimed at people who think that deconstruction is the only achievement that matters. She is primarily interested in the way critique undermines the real struggles for change by setting up a dualism between “them” who hold false beliefs, and “us” who always know best, who can always say “I told you so”. While her target is the deconstructionists, her critique is equally applicable to today’s academic Marxists who are fantastic at critique, but are incapable of traversing the divide between their much loved ‘fundamental contradictions’ and the messy real world of actually existing power struggles where decisions get made about policies and strategies. As Stengers so clear shows, modernity is quite happy to have these critiques around, for they are easily absorbed. What really subverts is action that changes things, and the co-production of knowledge that reinforces these kinds of “pre-cursive” transitions. The most memorable phrase of the day was when she said it is “so much easier to deconstruct than to foster”. Viva! (And thanks to Lesley Green from UCT for organising her visit to South Africa, for bringing her to Stellenbosch for a day, and to colleagues in Sociology’s Indexing the Human project for initiating the visit, and to Rika from CST for the logistics.)

Reflection on South Africa’s Renewable Energy Revolution

Yesterday I delivered a talk at a workshop of the Development Finance Institutions from Southern Africa, convened by the Chief Executive of the Development Bank of Southern Africa. I used the opportunity to reflect on and integrate two recent pieces of research – one by Lucy Baker from the UK and the other by Paul Gauche from the Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies here at Stellenbosch University. The group responded well to questions about the financialisation of the debt and equity capital that has triggered South Africa’s remarkable boom in renewables, despite the fact that government is more interested in coal, nuclear and fracking. However, none of the DFIs had ready answers to the problem of a disconnect emerging between the eventual owners of the debt and equity and the projects on the ground, but more importantly the inherent risks of a speculative bubble which if it bursts will really harm the sector before it can get strong enough. For the talk go to the Talks drop down menu on my website for recording plus powerport, or download here just for the talk: https://soundcloud.com/user-825958953/session-1

Africa really is changing

Over the weekend I read through the publications of an academic who is up for promotion at the University of Ghana. Although as a reviewer I had to pay attention to the usual details that matter to academics (methods, theory, etc), reading his incredibly detailed research on public participation and political processes during the democratic period since democratisation in 1993 was really quite inspiring. It reminded me once again how little the world (and especially South Africans) know about how drastically things have changed in Africa over the past two decades. If they know anything, it is the so-called ‘Africa Rising’ discourse – high growth rates in some countries, massive Chinese investments, new infrastructures being built, oil being found – plus also, if they have traveled, the really crazy wild cities as millions survive in the informal settlements and traverse urban environments that lack basic infrastructures. But what is not known is how a new generation of African leaders have been systematically assembling the political and institutional infrastructures of relatively stable political systems, some of which are actually quite democratic in a messy inconclusive way. For many who see all this from a ‘Western’ liberal democratic perspective, it all looks a bit strange and smacks of old-style African patronage politics. (And, of course, they conveniently ignore the profound contradictions of their own so-called ‘Western’ liberal democracies.) But what they are not seeing is how spaces now exist for participation in policy processes, local planning and active citizenship within the broader media environment (traditional mass media, but also electronic self-managed mass communications) that may well be irreversible. Out of the increasingly educated e-savvy urban youth cultures is emerging a complex set of exertions and energies that will inexorably widen these spaces, creating opportunities for new political formations and leaders to emerge. As always happens in Africa, what’s emerging is always difficult to see because we wear the wrong lenses to see them. But while we are not seeing, other things are happening that will eventually surprise us all. Watch this space.

An amazing week in Durban

Posted on FB on 13 September 2015: Sustainable Urbanization – a global South perspective. An amazing five days has just come to an end here in Durban. Wednesdeay through to Saturday was spent facilitating a session on Sustainable Urbanization focussed on the theme ‘modes of urban governance’. Incredible group of about 18 researchers from all regions (mainly global South, but with 2 from the USA, and 1 from Switzerland). This was the third seminar of its kind convened by International Social Science Council – I co-facilitated the first one in Quito, and this one here in Durban, but missed the one in Taipei. All three groups came together today at the World Social Science Forum to present summaries of their discussions. Very inspiring stuff – empirically rich, theoretically sophisticated, radical and action oriented.

Themes and papers from the Sustainable Urbanization seminar in Durban:

Thematic session 1: Climate Change and Governance

Aakriti Grover: Inter-linkages between land use/cover, air pollution, Urban Heat Island and human health: perspectives on urban governance in Delhi, India

Lorena Pasquini: Challenges and success in mainstreaming climate change adaptation in urban local government: a City of Cape Town case study

Thematic session 2: Climate Change/ Environmental Justice /

Sustainability

Saleh Ahmed: Transformative Urban Politics in the Megacities of the Global South: Focus on the Environmental Justice Movement in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Isabelle Anguelovski: Inclusive approaches to urban climate adaptation planning and implementation: Lessons from municipal experimentations

Alisa Zomer: Evaluating equity and governance in sustainable cities: Analysis of 100 Resilient Cities in China, India, and the United States

Thematic session 3: Land Use/ Agriculture/Governance

Tracy-Ann Hyman: Relocation or renewal? The case of Mona Commons, St Andrew, Jamaica

Kareem Buyana: Collaborative Sub-urban Transformation for Land Use Compatibility in Africa

Uchendu Chigbu: Tackling the challenges of urban poverty through “land-use planning for tenure security”: steps and activities for action in Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Thematic session 4: Urban Development/ Inclusive Development

Alice Hertzog: Avenues in the Tropics: Trans-disciplinary Tools for Emerging Cities

George Kinyashi: Retrospection of Private-State-Citizen Spatial Planning Financing Model in the Global South: Potentials and Limitations

Andre Ortega: Trajectories of Peri-Urban Futures: Mapping spaces of inequality, social justice and sustainability in Manila’s Peri-Urban Fringe

Ruishan Chen: Challenges of China’s Urbanization and the Promise of New-type Urbanization

Thematic session 5: Urban Poverty/ Governance

Karolina Luckasiewicz: Urban poverty, neighborhoods and social capital in NYC.

Martin Maldonado: From Dumpsite Scavenging to Waste Management Systems. Political Implications for Urban Governance in the Interior of Argentina

Thematic session 6: Urban Environmental Sustainability/

Housing/ Governance

Olumuyiwa Adegun: Reducing inequality, ramping up environmental quality: Just sustainability

in co-produced informal settlement upgrading in Johannesburg

Collins Adjei Mensah: Towards environmental sustainability in African cities: Addressing the governance inefficiencies on urban green spaces in Kumasi, Ghana

Hayley Leck: Local authority responses to climate change and urban challenges in South Africa – transcending administrative boundaries

Reflections on my life work in light of future opportunities

Stellenbosch University has asked systems biologist Prof Jannie Hofmeyr and myself to be the Co-Directors of a new Stellenbosch University ‘flagship’ initiative called the Stellenbosch Centre for Complex Systems in Transition (CST). This will bring together three core themes: complexity thinking, sustainability science and transdisciplinary research methodologies. The hope is that it will be funded in part by Stellenbosch University, and in part by the National Research Foundation, plus project funding from a range of sources. Besides our general conceptual project to build a framework that synthesizes complexity, sustainability and transition from a transdisciplinary perspective, we have three empirical case studies: water systems with a focus on the Breede River (in partnership with the Water Institute and Faculty of AgriScience), embedded Photovoltaic systems for domestic households across South Africa (in partnership with Centre for Renewable and Sustainable Energy Studies), and peri-urban food systems (in partnership with the Sustainability Institute and the FoodLab). We met last weekend to dream and strategise, followed by a three day workshop with Dave Snowden on how to use his Sensemaker tools for conducting qualitative research from an applied complexity perspective. At the weekend we agreed to each sketch out what we think our ‘core body of work’ is about. This is what I found myself writing out:

“My core interest is in the dynamics of transitions that over time and at different scales unevenly and in non-linear easily reversible ways result in a fundamental structural change in the nature of societal organization and its concomitant relationship to natural systems. At the temporal scale there are the metabolic shifts from the hunter gatherer societies to agricultural societies starting some 13000 years go, and still incomplete (there are still hunter gatherers); and then the shift from agricultural to industrial societies that started some 250 years ago, and also still incomplete (there are still predominantly agricultural societies); and the start now of the shift from industrial societies based on fossil fuels and resource exploitation to sustainable societies that will probably take a century, and will not complete itself either. At the scalar level I am primarily interested in the massive shift in population from predominantly rural to predominantly urban environments in the global South over a mere 8 decades, with 50% of what is predicted to be urban in 2050 still to happen over the next 4 decades globally. These are all structural shifts – the metabolic shifts from agricultural to industrial, from industrial to sustainable, and the structural economic shifts over the five cycles of industrial growth and decline since the start of the industrial revolution – we are midway through the 5th, and the 6th is starting that fuses with the 3rd metabolic revolution; and of course the spatial shift that is also very structural. What I am really interested in is how the transitions took place, and what this means for our understanding of how we can accelerate the transition that needs to happen now (see my 2013 paper on this). This is why I am interested in the micro-dynamics of societal and institutional actors, and the non-human actors (in the Latourian sense) with whom the social and institutional either consciously or unconsciously interact (hence the importance of the 4 films from the Food Revolution project). I am particularly interested in cities because this is where we find particularly intense interactions between societal and institutional actors and their ecological counterparts giving rise not only to alternative visions to drive the global transitions (as a kind of sum of the local transitions, but also more than the sum). And at the centre of these interactions is the built environment – the artefacts of modernization that we have constructed on a massive scale, all made possible by energy from fossil fuels, which is coming to an end. And so, out of crisis, like always, emerges the dynamics of innovation and transformation that underpins the emergent outcomes we call ‘new paradigms’. However, this time round it is not happening because a great thinker came up with a great new way of thinking about the world – there is no Galileo, no Newton, no Adam Smith, no Marx, no Keynes, no Bateson, no Shakespeare, no Hobbes or JS Mill. Following Castells, the IT revolution gave birth to a new mode of social organisation – the network, that is equal in significance to a Weberian bureaucracy or the joint stock company. We now work within this environment that Castells refers to as making possible “self-managed mass communication”, i.e. mass communication no longer emanates from a powerful centre. The future, therefore, is being made out of unprecedented and increasingly accelerated modes of collaboration – think of the Amsterdam Declaration of 2001 signed by scientists from over 100 countries to create the Earth-System Science Partnership, or how the IPCC works, or how the SDGs were formulated, and thousands of other global networks that are reshaping every day how things look. Hence my interest in anticipation defined at its core as the ‘evolutionary potential of the present’ to used Snowden’s words. And therefore the incredible significance of the sensemaker technology for gathering stories in a way that bridges the age-old gap that social scientists have always been plagued with, i.e. the gap between qualitative information derived through dialogue and generalisations that need to relate to knowledge imaginations that assume validity is what can be measured and/or repeated. Many just scrapped the problem by dismissing it as irrelevant, hence deconstructionism. But the other way is sensemaker, and equivalent approaches – mass collections of stories that can be patterned and communicated back into the global IT-based collaborations that are transforming the world. While I want to continue to work on cities and their dynamics of transition, and also on the metabolic transition with my colleagues in the International Resource Panel (see my overview of this work), I also want to work with the World Academy of Art and Science on the development of a New Economic Theory that at its core must be driven by what I call ‘realworldism’, i.e. instead of what economics is now, i.e. extreme reductionism (rooted in the notion of the rational individual), translated into beautiful mathematically elegant models, and projected back onto to society based on the assumption that the models accurately reflect the real world (primarily because of the neo-classical theory of price, i.e. that price reflects real value, ultimately). An alternative must be TD-type thinking to build new kinds of models that are derived from the COMPLEXITY of real world dynamics – that, to me is the key to a new economic theory and paradigm.”

Recent Comments